Le Camel Site (Arabie saoudite)

Comme son nom l’indique, le site est dédié aux camélidés, qui sont inextricablement liés à l’histoire et aux développements socio-économiques de l’Arabie. Utilisé pour le transport des marchandises dans les zones désertiques, ou pour de nombreux besoins de la vie quotidienne (lait, viande, bât, laine, etc.), le dromadaire est avant tout le plus noble et le meilleur compagnon des populations de la péninsule arabique. Le Camel Site est, en quelque sorte, un hommage de l’homo sapiens à cet animal fabuleux. Le site se distingue, dans le contexte désertique du nord de l’Arabie, tout d’abord par la technique de représentation employée (haut et bas-relief) mais également par la qualité de la représentation naturaliste, ou encore par la monumentalité des reliefs animaliers.

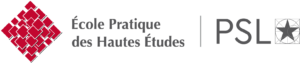

Relief de dromadaires sur un bloc tombé de la façade, au Camel Site. Fallen boulder with camel relief, at the Camel site, © Camel Site Archaeological Project, Guillaume Charloux

Situé au cœur du bassin de Sakaka, dans une région désertique au nord du Nafud, le Camel Site se compose de trois éperons rocheux allongés (A-C du sud au nord) orientés est-ouest, d’une hauteur maximale de 8-10 m et d’une longueur de 70-80 m. Le grès beige-orangé des rochers dans lesquels ont été sculptés les reliefs est malheureusement de mauvaise qualité, très sensible à l’érosion éolienne et se détache par blocs de la façade.

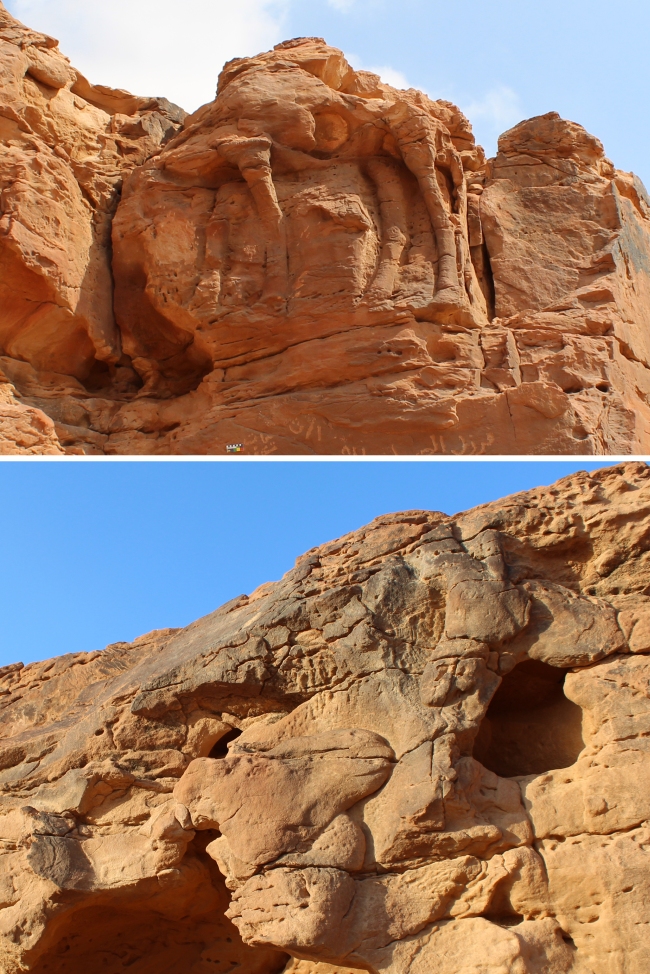

Nous avons identifié une concentration très dense de reliefs (21 bas et hauts reliefs grandeur nature) sur les parois des éperons, notamment des éperons A et C. Les 17 dromadaires et 5 équidés (ânes sauvages ?) que compte aujourd’hui le site sont célébrés dans leur espace de vie naturel, par la main de l’homme, mais étonnamment sans que ce dernier soit représenté et sans inscription. Si les animaux sont principalement représentés les uns derrière les autres, en file indienne, on observe également des rencontres entre espèces et peut-être des scènes de pâturage.

Ces panneaux monumentaux ont été sculptés à l’aide d’outils lithiques par différents individus, au vu des multiples styles visibles. Cependant, les sculptures partagent des caractéristiques communes telles que la représentation naturaliste du profil, la description détaillée des yeux, des narines, des oreilles et de la bouche, et des détails anatomiques tels que les muscles et les os des jambes. Les effets de mouvement et de perspective sont saisis dans la représentation d’une jambe devant l’autre, les jambes d’un côté passant par-dessus celles de l’autre côté de l’animal.

Relief grandeur nature d’un chameau et d’un équidé du Camel Site. En haut : relief d’un chameau de profil montrant son flanc et quatre pattes (panneau 11). En bas : dromadaire (à gauche) et équidé (en haut à droite) face à face (panneau 2). Naturalistic and life-sized camel and equid reliefs from the Camel Site: top) camel relief showing the side and underside of the body with four legs (Panel 11); bottom) camel (left) and equid (upper right) facing each other (Panel 2), © Camel Site Archaeological Project, Maria Guagnin

La datation des reliefs

Bien que l’art du haut-relief soit très répandu au Proche-Orient, les seules œuvres connues auxquelles on peut les comparer (en termes de sujet, de taille et de technique de bas et haut-relief) sont les deux caravanes de dromadaires du Siq à Pétra, datant de la période nabatéenne. On a donc d’abord émis l’hypothèse d’une datation contemporaine de la période nabatéenne, qui s’est avérée erronée. Nos recherches récentes ont révélé que ces reliefs datent principalement de la période préhistorique (néolithique), il y a environ 7 500 ans. Cette datation est basée sur une série d’études, combinant des données provenant du terrain autour des reliefs et des examens détaillés des sculptures elles-mêmes. Un sondage effectué sous un relief a livré du matériel lithique du néolithique final, ainsi que des ossements qui ont pu être datés par radiocarbone. L’examen a été complété par la datation OSL des sédiments présents sous un relief effondré il y a plus de 4 000 ans. Ces recherches et d’autres relevés de surface ont été complétés par diverses analyses : étude macroscopique de la technique de taille des reliefs (réalisés avec des outils en pierre et non en métal) et expérimentations associées, datation des patines à l’aide d’un analyseur XRF portable, examens stylistiques approfondis et recherche de fragments et d’outils à la base des éperons rocheux. À l’issue de ces investigations, il apparaît que les sculptures du Camel Site figurent parmi les plus anciens reliefs animaliers grandeur nature connus à ce jour.

La symbolique des reliefs du Camel Site

Plusieurs informations complémentaires corroborent la probabilité que le Camel Site avait une fonction symbolique, voire cultuelle : la singularité du site, la taille et la qualité impressionnantes des reliefs, leur concentration sur seulement trois éperons, l’absence quasi-totale de gravures ultérieures, la présence d’anciennes cupules et rainures tracées à la main ou avec des galets sur le corps des animaux (notamment pour récupérer de la poudre à usage médicinal ou autre) ainsi que l’existence d’une tradition de gravures naturalistes de dromadaires grandeur nature dans la région. Ces quelques éléments interrogent le visiteur et les chercheurs : le Camel Site était-il un sanctuaire à ciel ouvert dédié aux camélidés et aux équidés sauvages ? Et/ou était-il un lieu de rencontre symbolique pour les populations préhistoriques locales, comme nous le pensons aujourd’hui ?

English version

Discovered in 2016, it has been studied by a Saudi-French mission since the end of 2018: the objective is to improve our understanding of the archaeological context, dating and function of the site, but also to contribute to its protection.

Located in the heart of the Sakaka basin in a desert region north of the Nafud, the Camel site takes the form of three elongated rocky spurs (A-C from south to north) oriented east-west, about 8-10 m high at most, and 70-80 m long. The beige-orange sandstone of the rocks in which the reliefs were sculpted is unfortunately of poor quality, very sensitive to wind erosion and detached by blocks from the façade.

A very dense concentration of reliefs (21 life-size bas- and high-reliefs) has been identified on the walls of the spurs, notably Spurs A and C. The 17 dromedaries and 5 equids (wild ass?) that the site counts today are celebrated in their natural living space, by the hand of man, but surprisingly without his presence or inscription. The animals are generally part of processions, but also of encounters between species and perhaps moments of grazing.

These monumental panels appear to have been carved by different individuals, based on the multiple styles visible. Nevertheless, the carvings share common features such as naturalistic profile representation, detailed depictions of the eyes, nostrils, ears and mouth, and anatomical details such as muscles and leg bones. In addition, the effects of movement and perspective are captured in the depiction of one leg in front of the other, with the legs on one side passing over those on the other side of the animal.

Although high relief art is widespread in the Near East, the only known comparisons (in terms of size and technique of low and high relief) are the two camel parades of the Siq in Petra from the Nabataean period. This comparison led to an initial hypothesis of contemporary dating to the Nabataean period, which turned out to be erroneous. Our recent investigations have revealed that these reliefs date mostly from the Prehistoric (Neolithic) period, about 7500 years ago. This proposal is based on a series of studies, combining both field data around the reliefs and detailed examinations of the sculptures themselves. A test pit under a relief yielded lithic material from the Final Neolithic period, as well as bones that could be dated by radiocarbon 14. The examination was completed by the OSL dating of the sediments present under a collapsed block comprising a relief, more than 4000 years ago. In addition to these investigations and other surface surveys, various analyses were carried out: a macro study of the cutting of the reliefs (made with stone tools and not metal) and related experiments, dating of the patinas using an XRF portable, extensive stylistic examinations and the search for fragments and tools at the base of the spurs. At the end of this description, it appears that the sculptures from the Camel Site are among the oldest life-size animal reliefs known to date.

Finally, a probable symbolic or even cultic function of the Camel Site is now supported by a series of complementary information: the uniqueness of the site, the impressive size and quality of the reliefs, their concentration on only three spurs, the almost total absence of later engravings, the presence of ancient cupules and grooves traced by hand or with pebbles on the bodies of the animals (notably to recover a powder for medicinal or other purposes) as well as the existence of a tradition of engravings (but not in relief) of life-size and naturalistic dromedaries in the region. These few elements still raise the question: was the Camel Site an open-air sanctuary dedicated to camelids and wild equids? And/or was it a symbolic meeting place for the local prehistoric populations?

Research program

Fieldwork and research were funded by a grant from the Gerda Henkel Foundation (Grant No AZ 43_V_18, to MG and GC), the CNRS (to GC), Labex Resmed ANR-10- LABX-72 / ANR-11-IDEX-0004-02 (to GC), the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the French embassy in Riyadh (to GC), the Cefrepa (to GC), the Dahlem Research School at Freie Universität Berlin (to MG), and the Max Planck Society (to MG and MS). AMA acknowledges the support of the Research Center at the College of Tourism & Archaeology, King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Etude des traces d’outils du panneau 2 par l’ingénieur Franck Burgos (CNRS). Panneau sculpté en bas-relief, représentant un dromadaire (Camelus dromedarius) de profil, levant la tête vers un équidé se tenant sur sa droite. Tool marks on Panel 2 being inspected by CNRS engineer Franck Burgos. This engraved panel in low-relief, representing a dromedary (Camelus dromedarius) in profile, raising its head towards a standing equid to its right. © Camel Site Archaeological Project, Guillaume Charloux.

Articles

Charloux, G., Guagnin M., Petraglia M., & AlSharekh A., 2022, « A rock art tradition of life-sized, naturalistic engravings of camels in Northern Arabia: new insights on the mobility of Neolithic populations in the Nafud Desert ». Antiquity, 5 septembre 2022, p. 1‑9. https://doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2022.95.

Guagnin M., Charloux, G. & AlSharekh A., 2022, « Monumental Sandstone Reliefs from the Neolithic: New Insights from the Camel Site in Saudi Arabia ». The Ancient Near East Today X, no 7 (1 juillet 2022). https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-03728911.

Hilbert, Y. H., Clemente-Conte I., Crassard R., Charloux G., Guagnin M., et AlSharekh A.M., 2022 « Traceological Analysis of Lithics from the Camel Site, al-Jawf, Saudi Arabia : An Experimental Approach to Identifying Mineral Processing Activities Using Silcrete Tools ». Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences 14, nᵒ 5 (26 avril 2022), p. 93. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12520-022-01559-6

Charloux G. (coord. scient.), 2021, L’art rupestre en Arabie. Une histoire oubliée des peuples du désert. Dossiers d’archéologie n°407, septembre-octobre 2021.

Guagnin M., Charloux G., AlSharekh A. et al., 2021, « Life-sized Neolithic camel sculptures in Arabia : A scientific assessment of the craftsmanship and age of the Camel Site reliefs», Journal of Archaeological Science : Reports. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jasrep.2021.103165

Charloux G., Guagnin M. & Norris J., 2020, « Large-sized camel depictions in western Arabia : A characterisation across time and space », Proceedings of the Seminar for Arabian Studies 50, p. 85-108.

Charloux G., Guagnin M., Alsharekh A.M., 2019, « Il « Camel Site ». Rilievi rupestri di cammelli a grandezza naturale nel deserto Arabo », in Alessandra Capodiferro ; Sara Colantonio. Roads of Arabia. Tesori archeologici dell’Arabia Saudita, Electa, p. 63-73 (Ita.) ⟨hal-02500422⟩

Charloux G., Guagnin M., Alsharekh A.M., 2019, « The Camel Site. Rock reliefs of life-sized camels and equids in the Arabian desert », in Alessandra Capodiferro ; Sara Colantonio. Roads of Arabia (Rome), Electa, p. 63-73 (Ang.) ⟨hal-02500392⟩

Charloux G., al-Khalifa H., al-Malki T., Mensan R. & Schwerdtner R., 2018, « The Art of Rock Relief in Ancient Arabia. New Evidence from the Jawf Province », Antiquity 92/361, 2018, p. 165-182 ; https://doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2017.221